Special Briefing: Immigration reform stalls in Parliament

After hinting at alignment with Chega, the government yesterday followed PS advice and sent nationality and immigration bills to committee without a vote. Why the U-turn? What does it mean?

Yesterday, Parliament debated the government’s proposals to amend the nationality law and tighten immigration rules.

The session was heated, with Chega leader André Ventura reading aloud the names of foreign children attending public schools in Lisbon, an act that drew sharp criticism from across the political spectrum.

In the end, Parliament approved in its first reading the creation of a National Unit for Foreigners and Borders (with Chega voting in favor and the PS abstaining), rejected the Left Bloc’s (BE) proposal to end golden visas, and, following the PS’s earlier suggestion, sent the nationality and immigration bills to committee without a vote.

It is worth noting that on Thursday, the idea of bypassing a vote and sending the bills directly to committee had been proposed by the Socialist Party (PS), but did not receive support from the ruling coalition.

At the time, the parliamentary leader of the leading Social Democratic Party (PSD), Hugo Soares, rejected the suggestion, arguing that immigration legislation was a priority and that parties should take a position now.

Why the U-turn? And what does it mean?

How it happened?

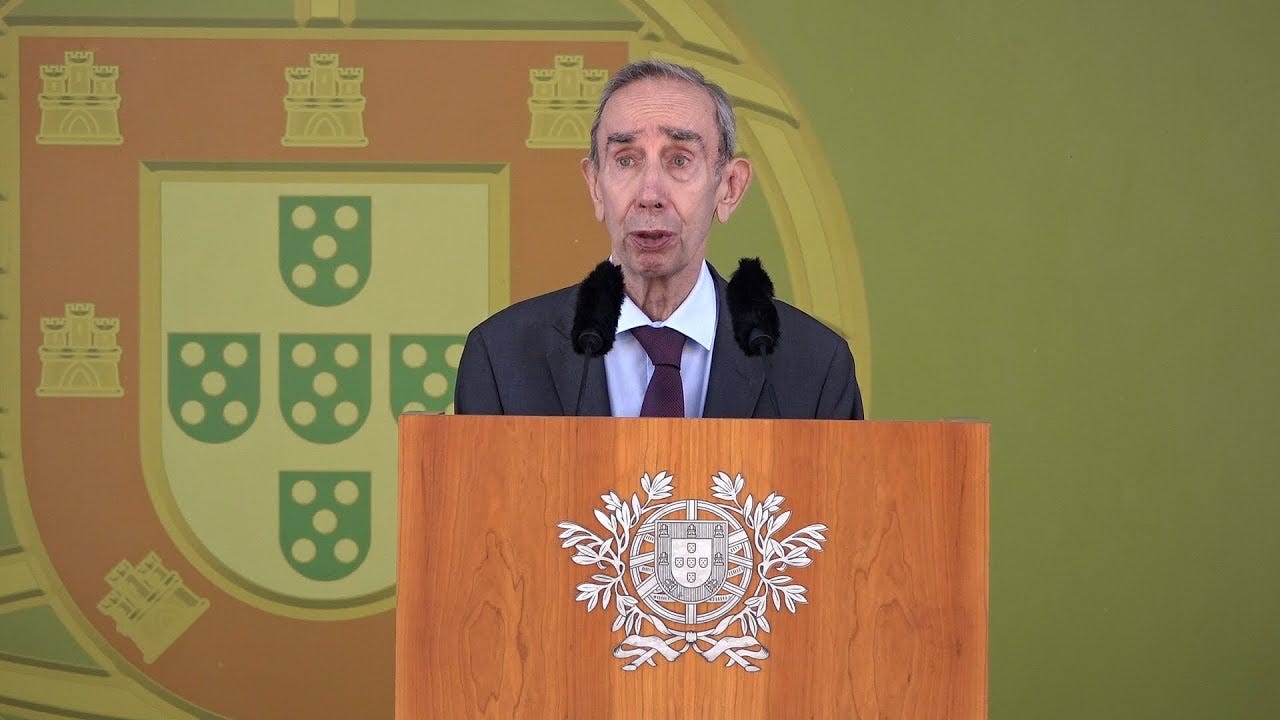

In yesterday’s parliamentary session, the Minister for the Presidency, António Leitão Amaro, expressed openness to Chega’s leader regarding a shared path toward approving the proposed changes to the nationality and immigration laws.

In reply, André Ventura said: “Times have changed, because the Portuguese voted for change in the last election (referring to the May 18 elections, in which Chega emerged as the second largest party in Parliament).”

He then highlighted the amendments that Chega wants to include in the new nationality bill: proof of Portuguese language skills, extending the current 10-year limit for revoking nationality acquired through naturalization, and automatic loss of nationality in cases of serious crimes.

In response to Chega’s demands, the Minister for the Presidency simply said he was confident that “there is a path for Parliament to approve measures.”

He then issued a warning to Chega’s leader, stressing that “the line that cannot be crossed is the Constitution.”

“None of us can pass an unconstitutional law. That means no life sentences, including loss of nationality, and no automatic revocations that violate the Constitution,” he emphasized.

Why the sudden concern with the Constitution?

Two key reasons:

First, a warning from the President. As reported in yesterday’s Friday Briefing, President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa made it clear that, once the final legislation reaches him, his priority will be to assess any potential constitutional issues. He acknowledged that there may be provisions that will raise constitutional doubts, for which “it’s better to have a definitive ruling from the Constitutional Court, because otherwise, each court might interpret them differently.”

Second, Expresso reported yesterday that Jorge Miranda, a Constitutional Law professor known as the “father” of Portugal’s current Constitution, together with Rui Tavares Lanceiro, another law expert, issued a legal opinion on the government’s proposals (at the request of law firm Liberty Legal, which specializes in immigration and citizenship). His analysis concludes that several elements in the draft laws restricting access to nationality and changing immigration rules “raise constitutional doubts,” while others are outright “inadmissible” under the Constitution.

What are the key constitutional concerns?

The legal opinion criticizes the government’s decision to retroactively apply its proposed nationality law changes to June 19, the day its program was approved in Parliament. Applications submitted from that date onward would be assessed under the new, stricter rules. The government justified the move by citing a surge in applications aiming to benefit from the current law. However, the opinion argues this violates the constitutional ban on retroactive laws that limit rights and undermines Parliament’s authority, as the decision was made before the reform was even debated.

A key constitutional concern is the proposed change to how residency periods are calculated for nationality applications. The government wants to double the required time from five to ten years and start counting only from the date a residence permit is granted, not from when the legalization request is submitted. The legal opinion states that this provision is “constitutionally inadmissible” since it creates legal uncertainty, violates equality and human dignity, and unfairly shifts control to the state. Two people applying on the same day could face vastly different timelines, with no clear justification.

Concerning family reunification, the legal opinion challenges the government’s decision to restrict urgent legal actions against the AIMA. According to the opinion, this measure represents an unjustified restriction on access to justice and violates the principle of proportionality. The authors argue that “the excessive backlog of administrative cases stemming from AIMA’s actions or omissions is the result of the agency’s own dysfunction, not of citizens legitimately exercising their fundamental rights.”

In their analysis of the possibility of revoking citizenship from naturalized individuals on legal grounds, Jorge Miranda and Rui Tavares Lanceiro state in their opinion that the measure “raises the potential violation” of the principles of equality, proportionality, and universality, as it introduces a distinction between Portuguese citizens by birth, who can never lose their citizenship, and those who acquired it through naturalization.

What does this mean?

The outcome of the lengthy debate suggests the government is still trying to play both sides: keeping the Socialist Party (PS) engaged while stopping short of fully aligning with Chega, even as its proximity to the far right becomes increasingly apparent.

But the risks of this strategy are high, and the outcome remains uncertain.

On one hand, Chega may toughen its stance in upcoming negotiations to argue that the government isn’t truly committed to curbing immigration, reinforcing its narrative as the only genuinely anti-immigration force.

On the other, by showing willingness to work with Chega on such a sensitive issue, the government risks alienating centrist voters, especially given Luís Montenegro’s repeated pledges not to align with the far right.

The PS is already capitalizing on this. On Saturday, party leader José Luís Carneiro accused the government of running “into the arms of the far right” in its first parliamentary move, and of focusing on “virtual problems” rather than real ones.

Ultimately, this raises the likelihood that the proposals will be significantly altered or may fail to secure enough parliamentary support to pass at all.

What happens next?

After the vote, André Ventura told journalists he had reached an agreement with Prime Minister Luís Montenegro to conclude the legislative process “before the holidays,” aiming to “set limits on nationality, immigration, and the entry of people into the country.”

He said the commitment was to work over the coming days to ensure that the bills on immigration, family reunification, and nationality are finalized before the end of the legislative session, referring to a meeting with Montenegro last Thursday.

However, two days earlier, the PSD had already requested in Parliament that the government’s bills—and related proposals from other parties—be fast-tracked in committee, allowing for a final vote by July 16, the last scheduled plenary session before the summer break.

If approved, the bills will then go to the President, who has 20 days to review them. In the case of the Nationality Law, President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa may request a ruling from the Constitutional Court.

Bottom line: it remains unclear if, when, and in what form the proposed measures will come into force.

Thoughtful and clear analysis of this situation. Obrigado.

So grateful for your analyses!

Eerily, at the same time Portugal is debating birth versus naturalization citizenship, Trump’s U.S. has already decided that naturalized American citizens are invalid.

One wonders how this is factoring in Chega’s strategy and alignment with America’s current authoritarian bent.