Parliament's November 25 ceremony marred by controversy

As Portugal marks the 49th anniversary of the November 25, 1975, military operation, the commemorations have sparked political and ideological divisions.

What?

As Portugal marks the 49th anniversary of the pivotal November 25, 1975, crisis, the commemorations are sparking political controversy.

The decision to celebrate the event in Parliament was approved only by right-wing parties - the ruling AD, the liberals (IL) and far-right Chega. The Socialists (PS), the Left Block (BE), the communists (PCP) and ecosocialist (Livre) voted against the ceremony.

Parliament has planned a ceremony modeled on the grand celebrations for the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution (April 25, 1974), a move criticized by some as divisive.

Both the PCP and the Associação 25 de Abril - an organization founded in 1982 by military officers who played key roles in the Carnation Revolution - have declined to participate, condemning what they see as an attempt to overshadow April 25’s significance.

Tell me more

The anniversary honors the end of the turbulent Processo Revolucionário em Curso (PREC, or “Ongoing Revolutionary Process”), a period marked by radical leftist influence and widespread instability following the fall of the Estado Novo dictatorship.

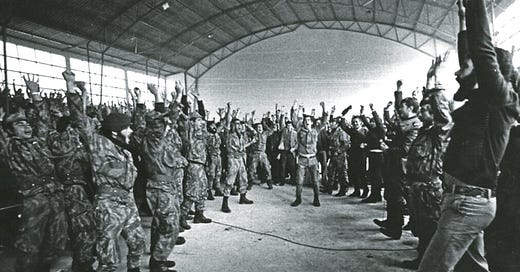

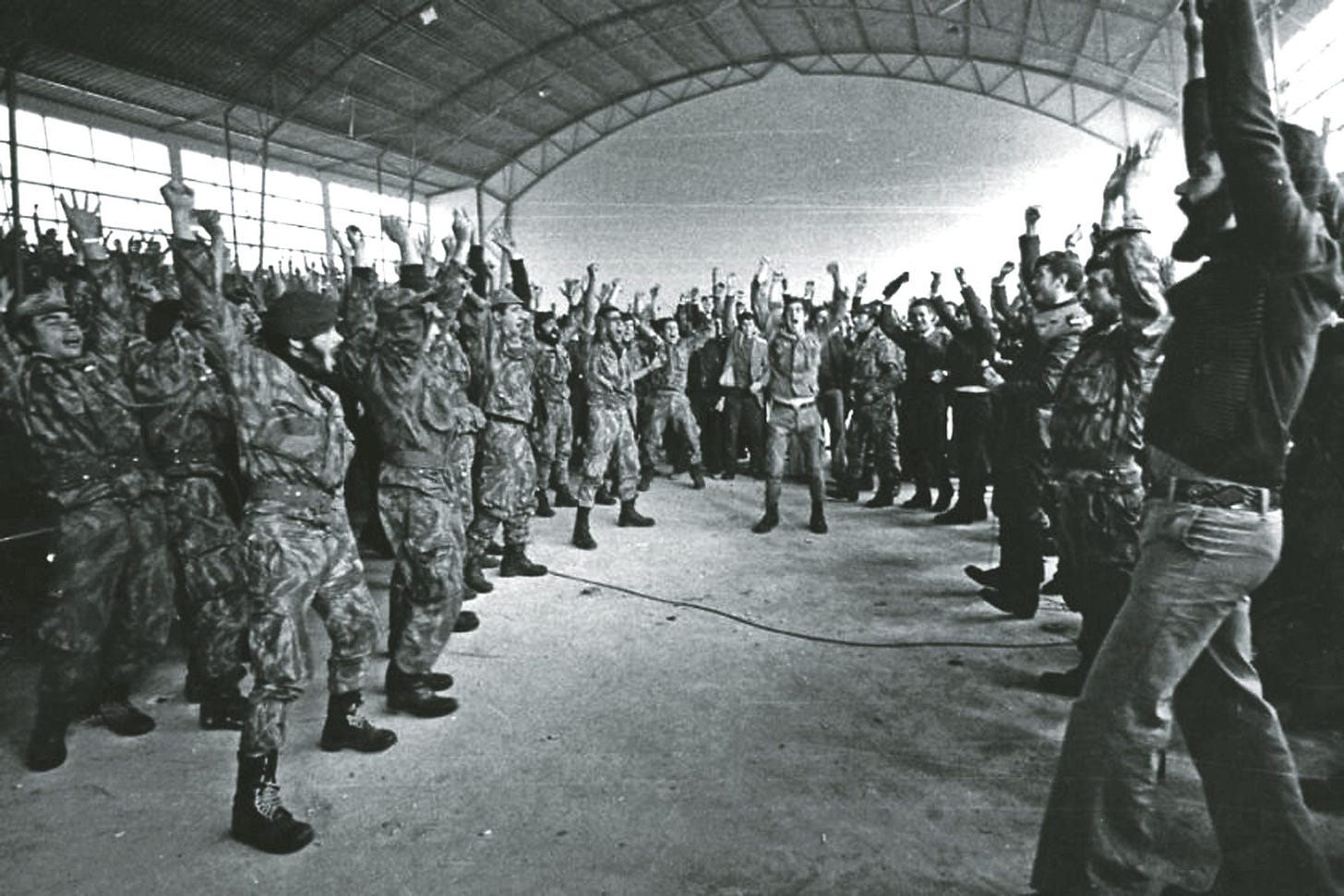

The November 25 crisis pitted radical left factions, supported by the Armed Forces Movement, against moderates like General Ramalho Eanes and the Group of Nine.

The moderates’ victory paved the way for Portugal’s transition to democracy but remains a contested event.

Supporters view it as a triumph for democratic stability, while detractors, including the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and the 25 April Association, argue it undermined revolutionary ideals.

Despite objections, the ceremony—backed by right-wing parties including PSD, CDS, Liberal Initiative, and Chega—will feature military honors, national anthems, and speeches from political leaders. Critics, however, warn that commemorating November 25 in this manner risks deepening ideological divides.

The debate underscores the enduring complexities of Portugal’s post-revolutionary history, as the nation reflects on its path to democracy and the unresolved tensions surrounding its transformative moments.

Background

After exiling dictator Marcelo Caetano, the Junta of National Salvation, led by President António Spínola, initiated negotiation with the African nationalist movements.

Independence was granted to Portuguese Guinea (as Guinea-Bissau) almost immediately after the revolution. The new regime abolished such instruments of repression as censorship, the paramilitary forces, and the secret police.

Spínola, who opposed rapid independence for the colonies without free referendums, resigned in September 1974, launched a countercoup attempt that failed (March 1975), and fled into exile.

Political and social instability prevailed through most of 1975. Radical military elements and leftist allies, including the Communist Party, gained control, prompting widespread social instability: over half a million refugees arrived from African colonies, strikes surged, while the Government nationalized industries and farmworkers expropriated latifundia especially in the Alentejo region.

Fearing a socialist shift, the U.S., under President Gerald Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, acted through the US embassy in Lisbon, instructing the American ambassador Frank Carlucci – later Secretary of Defense – to “vaccinate” Portugal against the communist disease (Read here a 2018 interview with Carlucci about the process, published in portuguese in the newspaper Expresso).